Three Things from Edmonton -- Episode 127: Meow! red, 1

As we wait for the mosquitos' reaction to all the rain of late, here are three things left behind tracks of happiness and gratitude this week.

Three Things, episode 127:

1. Meow!

It’s August 1997. We are at the Edmonton Folk Music Festival. From inside a portapotty near the children’s stage, I hear John Prine singing Hello In There. I am in the hot, polyurethane plastic confessional supervising one of our young sons who, I know, will, when we’re done, insist on going not to the stage Prine is at but back to the children’s area. In the battle of Gallagher Hill, it is Fred Penner triumphs.

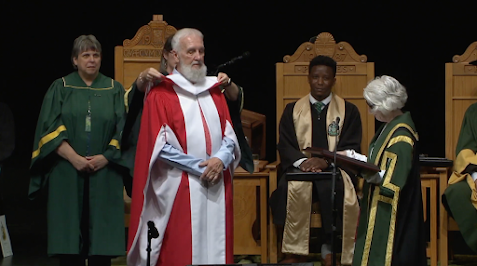

Dr. Fred Penner was back on stage at the Jubilee Auditorium last week. It was spring convocation at the University of Alberta. The chancellor, Peggy Garritty, had just made him an honorary Doctor of Letters. Penner told the grads about his younger sister, Susie. She was born with Down Syndrome. He remembered how they shared the joy of music. Her favourite LP record was the soundtrack from West Side Story.

“And that incredible, truly incredible music from Leonard Bernstein would get totally inside and capture Susie’s imagination,” he said. “I was in awe. I was truly in awe as I watched her become totally immersed in these beautiful, beautiful songs, often to the point of tears.”

Susie died in 1970, their father died a year later, and it was then that Penner, who had graduated with an economics degree at around the same time, described how a "calm and quiet introspection" found him.

Quiet is not something that you think of when you think of musicians. They add to the quiet, they take the quiet away, they make noise and sound. But before the music-making happens, the musician needs to hear a voice. Quiet is essential for that discovery. This was Penner revealing the birth of his art to the Education Class of 2023. I watched it three times on livestream. Penner recounted how it was music, not economics, that delivered the ringing feeling of being alive. Music, like the cat, kept coming back to him. As the song teaches, the danger was in sending the cat away. He learned to speak its language.

I now think that’s why in the song he asks us to pause and sing a meow of thanks for the gifts that return until we accept them for who we are.

2. Red

A couple of days ago I am pedalling in Lower Garneau as a red car pulls away from the curb, angles toward me, stops. The window rolls down and the driver yells at me for not being in the bicycle lane and then says that I am going to get run over. I am 100 per cent in the right here. The bike lane the driver is pointing to is a one-way lane in the other direction. The roadway I am in the middle of has an arrow for bikes. I remind the driver of the rules of the road, at which point I am screamed at for having no clue what I am talking about. Up goes the window and off goes the little red car. I collect myself in the car’s perfumed speech balloon of exhaust.

It’s unnerving to be screamed at by people who are screaming at an image of you. I have sympathy for those for whom the stakes are higher than mine as a bicycle rider. Selfishly, though, I wonder what I should say to these drivers in the moment. Nothing satisfies. A clever quip can be cruel. If I stumble and fumble out a response, I feel silly. Saying nothing seems to concede the point. I sometimes point to my phone and say see you on YouTube, but then I imagine getting hunted down and shot. I’ve gone to the police when I have felt my safety threatened. Typically, the police are not overwhelmed by the story of someone not injured. The politicians who give drivers a green light for this behaviour don’t admit their part. So, how best to react?

It struck me as I pedalled on through the University Farm that, maybe, I wasn’t asking the right question, that, maybe, I hadn’t done my basic communications work. I was trying to come up with the perfect key message for the driver before I had considered who my audience was. Was I really communicating with the person in the red car? Really? With any hope of changing that person’s behaviour? We communicate in these situations to change behaviour, not just to raise awareness, after all. Whose behaviour could I really change? Who was I really communicating with? Who should a key message really be directed at? My tentative answer: not the politicians, not the cops, not even the red car driver. I’m communicating with myself. Sure, I’m good if rude drivers see their errors. But my real goal is not to be taken along angrily for the ride. The moment is not as much a public opportunity to capitalize on as a private threat to be avoided. This is why, when the red car episode happens again, and it will, I will try to remember to simply ask a question. That question: Are we open to changing our minds? If yes, we can debate civilly. If no, I will move on. Either way, I hope that I will stop seeing red.

Next, I’ll work on how to react when I’m in the wrong.

Our grandson, Little Buddy, turned one year old last week. The families who jointly claim him gathered for a party at the Clareview Rec Centre. Wherever he goes in life, he started out as a north ender in Edmonton.

We sang happy birthday. I glanced at the gift table on which boxes wrapped in shiny paper sat. Like a skyline. Or a collection of aquariums. Or incubators. Little Buddy had a rough landing a year ago at the Grey Nuns Hospital. He spent the first days of his little life in Room 3209 in a neo-natal intensive care incubator connected to monitors and under tiny blankets and warming lights. He was in the care of nurses and doctors whose callings helped make real, one year later, a round of happy birthday in Multipurpose Room #2 on the other side of the city.

Many happy returns, Little Buddy.

Comments

Post a Comment